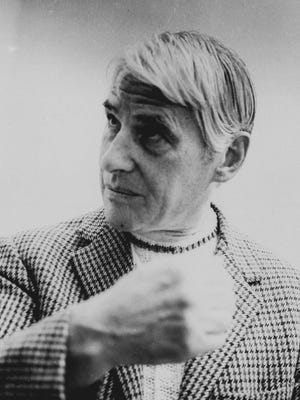

Artist Willem de Kooning dies at age 92

Editor's note: This article originally appeared in the March 20, 1997, edition of The Arizona Republic, one day after painter Willem de Kooning's death.

Willem de Kooning, considered one of the greatest painters of his time and a dominant figure in postwar art, died Wednesday in his East Hampton, N.Y., studio at 92.

His death was not unexpected, yet it was still shocking.

The artist had been ill and had suffered the ravages of Alzheimer's disease for more than a decade. His death takes from us the last giant of the movement that brought the center of gravity of the art world from Europe to America in the 1940s and '50s.

MORE: Stolen de Kooning painting turns up 31 years later

De Kooning's large abstract paintings were among the most influential in the century and helped define a style called Abstract Expressionism, which flourished in New York City during those years.

Along with Jackson Pollock, who died in 1956, de Kooning was the most prominent of the painters whose work was built of thick paint and busy brush strokes.

As a group, the Abstract Expressionists had many aims. Among them was the expression of emotion directly in color and shape rather than through narrative and subject matter: There was no mistaking their work for Norman Rockwell.

Their paintings are often as important for how they were made as for what results: Some, like Pollock, dripped paint onto floor-mounted canvas. The result was dubbed ''gestural art.''

De Kooning often worked in pure abstraction, but he is best known for his series of canvases depicting women with the ferocity of a mugging and the iconic force of a cave painting.

Old World craftsman

To see his work, with its swirls of color and scrapings, one might think he worked in a fury, but anyone who saw him paint knows that he approached his canvas with the calm deliberation of an Old World craftsman. He would make a mark with his brush, then step back and consider what he had done. A few minutes later, he would make another stroke and step back once more. It was a slow, painstaking process that mirrored the care of an ''old master,'' whose artistic heir he considered himself to be.

In fact, de Kooning was born in Rotterdam, Netherlands, in 1904. His father was a wine merchant and his mother a barmaid. After a tumultuous childhood, he found work as a commercial artist in Belgium. But in 1926, he stowed away on a steamship and made his way to America.

''I looked all over for the skyscrapers I always used to see in postal cards,'' he once recalled. ''I said, 'America, here I come.' And I made it.''

He was known as ''Bill'' to his friends and became a citizen in 1961, but he never lost his accent.

For a while, he made his living as a house painter, but he became friends with several young artists, including Stuart Davis and Arshile Gorky, with whom he shared a studio.

The Federal Art Project in 1935 gave him a chance to work on his art full time, and he began showing regularly. His first one-man show came in 1948 at age 44.

Early figures of men were succeeded by figures of women painted in glowing pinks and greens.

''Flesh was the reason why oil painting was invented,'' de Kooning once said.

He credited Pollock with the seminal accomplishment in Abstract Expressionism. ''Pollock broke the ice,'' he said.

But in the 1950s, de Kooning returned to the figure. He worked for three years on Woman I, which was bought by the Museum of Modern Art. Other ''Woman'' paintings followed.

De Kooning was never a theory-driven painter, although many around him were, and the critics who proselytized for abstraction often made elaborate philosophical justifications for the work. De Kooning frequently confounded them by changing directions, now painting abstractions, now painting figures again.

''To desire to make a style is an apology for one's anxiety,'' he once said. ''Style is a fraud.''

Acclaim follows

Recognition came from buyers as well as critics: His 1944 Pink Lady brought $3.63 million in an auction at Sotheby's in 1987. Two years later, his 1955 masterpiece Interchange sold for a stunning $20.6 million at the same house. Vintage works consistently sold for more than $1 million.

In the late '70s and early '80s, he seemed to have played himself out. But a new series of simpler, brighter paintings gave evidence to a partial rejuvenation. Others thought the new paintings just awful. They were called kitsch by some.

But recent shows in New York and Washington of the late paintings have generally turned that assessment around, and his late work is seen as astonishingly fresh and vivid.

But by the late '80s, it became clear that the painting was becoming highly variable. Alzheimer's disease and years of alcohol abuse slowed de Kooning down, although he continued to paint.

In 1989, a court appointed his daughter, Lisa, then 33, and lawyer John Eastman co-conservators of his assets, estimated at more than $7 million.

De Kooning was married in 1943 to fellow painter Elaine Fried. They separated later, and when he was 52 he had a daughter, Lisa, with Joan Ward. But he never divorced Elaine, and in 1978 she returned to take him in hand.

She helped him stop drinking and handled all his affairs until her death in 1989.