Polaroids, trucker hats, Geraldo: The story of topless doughnut shop in 1989

FORT COLLINS, Colo. — Men and women seeking topless rights for all have sparked one of the newest political movements to pick up steam in several U.S. states.

Variously called “topfreedom” or “Free the Nipple” — a crusade to “decriminalize” the female breast by allowing women to go topless in the same public places as men — has materialized across the country, with rallies in major cities, activist arrests in New Hampshire and a legal battle in the small community of Fort Collins, Colo.

One of its spiritual leaders is the singer Rihanna, who once told Vogue: “I have always freed the nipple.”

The fight in Fort Collins began in August 2015, when a group of advocates brought attention to the city’s public nudity ordinance, calling it unconstitutional and discriminatory toward women. As residents filed into the city council chambers and pleaded with area leaders to respect their values and keep women covered — a battle the anti-topless forces won — memories stirred. This had — in a different form many years ago — happened before.

Debbie Duz Donuts Timeline | Fort Collins Coloradoan

The same scrutiny once circled Debbie Duz Donuts, a topless doughnut shop that opened on the edge of Fort Collins in the summer of 1989. On its first day, years before topfreedom, a camera cut to one of the few females in the crowd, a short woman with cropped brown curls and big, owlish glasses.

Why had she chosen to be part of the day’s crowd?

“Because it’s only right!” she boomed. “Men can run around topless. Women should have the right, too.”

Free the Nipple organizers host free picnic

At the center of the divisive doughnut shop that made international headlines was an air conditioning specialist turned inventive entrepreneur who — even after all this time, the headlines, the lawyers and Geraldo Rivera — swears that most people still don’t know the whole story.

At 69, Dennis Cortese is known mostly around town as “the Debbie’s guy.” He’ll be the first to tell you that his fight to open a topless doughnut shop in Larimer County had nothing to do with women’s liberation.

Decked out in a Debbie Duz Donuts jacket with “Dennis” embroidered on the front and a white trucker hat from the shop resting on his head, Cortese talked recently about his unusual idea, which was born out of a Christmas Day chat with his three truck-driver brothers-in-law.

“We started getting some people talking when we mentioned that we were going to have topless waitresses,” Cortese added. “I mean, truck drivers. What are you going to have? A giraffe inside? Come on.”

Free the Nipple crosses the pond; British march topless

The plans Cortese submitted for Debbie Duz Donuts, just off of Interstate 25, included topless waitresses and the sale of adult movies, magazines and toys.

Barbara Trevarton, the manager of a neighboring mobile home park, immediately circulated a petition that received thousands of signatures. Soon she was fielding hundreds of phone calls supporting the opposition’s cause.

“Probably 100 a day,” she recalled

Concerned community members pleaded with the County Commission to stop the shop. In June 1989, more than 600 opponents flooded the Fort Collins High School gym for a rally, at which Sheriff Jim Black, now 71, referred to the doughnut shop as a “front for prostitution” and told the crowd, “I will do everything I can under the law to see that Debbie does not survive Fort Collins.”

What Black could do, it turned out, wasn’t much. Since doughnuts and coffee would be served, instead of alcohol, Debbie Duz Donuts couldn’t be regulated under the state’s liquor code, like the area’s sole strip club at the time, The Hunt Club (which closed in 2013 to become a church).

The community and county’s response to it all played out on the pages of the newspaper — in notices about a Debbie Duz NOT hotline for concerned citizens to call, in a full-page ad purchased by 200 residents and local businesses against the idea and in the letters to the editor either condemning or defending Cortese and his rights.

In some photos from then, protesters hold up signs that read “Do not be led into temptation” on one side and “NO SEX NAZIS” on the other.

The county ended up passing an ordinance restricting nude entertainment businesses later that year, but it was too late to stop Debbie’s.

“We couldn’t deny it,” former Larimer County Commissioner Daryle Klassen said. “The zoning was in place for a doughnut shop.”

After opening day in late July, headlines simply read “Debbie Duz It.” Its first day in business was a spectacle, as news cameras panned the dusty parking lot just outside of the then-sleepy college town. A sea of men in tank tops and trucker hats formed before noon, snaking around the modest former gas station.

Behind its covered windows, waitresses readied themselves for their first day. The dress code was simple: shoes, bikini bottoms and a smile.

“It’s kind of like this,” Black recalled last month. “If you have a banjo player coming to the center of town and start playing the banjo, everyone’s going to come.”

The circus didn’t truly come to town until three months after Debbie’s opened its doors. Geraldo Rivera, who had come off the Aryan brotherhood brawl that left him with a broken nose the year before, made a trip to Northern Colorado where he filmed a segment on Debbie’s for his show, Geraldo.

With constant coverage, word reached the shop’s target audience.

“It got out to the truck-driving community and everyone made arrangements to stop at Debbie’s,” said Fort Collins resident and former Debbie’s regular Norm Cook, 77. “‘I’ll meet you at Debbie’s!’ You know?”

Topless in Times Square: Column

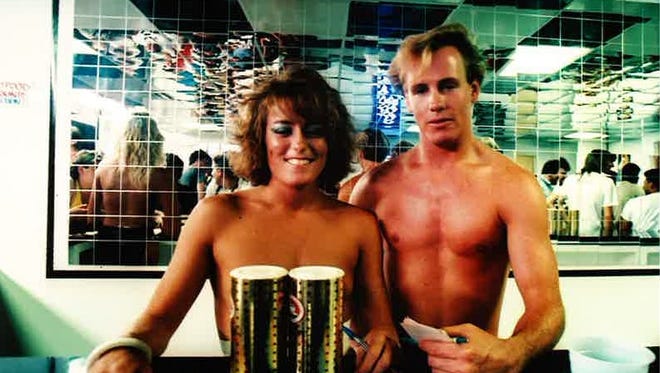

The shop itself was no bigger than a McDonald's, Cook said, with stools, mirrored ceilings, coffee, doughnuts and, eventually, other breakfast foods. For $25, you could have a picture taken with the waitresses and posted on a bulletin board. Now sitting in a box in Cortese’s apartment, the faded Polaroids show images of semi-trucks lining Debbie’s parking lot, two token male waiters in underwear posing with female customers and 18-year-old Connie Casey sandwiched among a group of truckers.

Casey, now a 44-year-old grandmother, openly talks now about her days at Debbie Duz Donuts. She’ll even tell you about the little tattoo on her chest: a small C and a J with a heart in the middle showing off her then-initials.

“When people would ask me whatever my name was, I would tell them that my name was C.J. and that I was the only topless waitress there with a nametag,” Casey said coolly, and in a Southern drawl, over the phone from her native North Carolina.

Casey said there was one point where bodyguards were following waitresses home for extra security. Sundays brought protesters out in full force, and Black never became a fan, she added.

Now, with 26 years between him and the unlikely, yet defining, issue of his career, Black chuckles a bit when asked about it.

“I look at all the really great things we did as sheriff and people always bring up Debbie Duz Donuts,” he said.

Toplessness wasn’t ultimately Debbie’s undoing. The sheriff’s office instead received a tip that drugs were being sold on the property. Cortese was arrested after the sheriff’s office said he was involved in two undercover drug buys, which he still denies. That night, on April 4, 1990, Black and a handful of deputies marched through Debbie’s and closed its doors. An outstanding tax debt with the Colorado Department of Revenue kept them shuttered.

Cortese was sentenced to two years’ probation for obtaining a controlled substance through fraud or deceit. He filed a lawsuit, which stretched on for years and accused the sheriff’s office of corruption. It was dismissed in 1995.

Debbie’s never sold another doughnut after its closure in 1990. Its total run was a little more than eight months.

Once a town’s most controversial doughnut shop, it is reduced to a small collection of memorabilia and photographs in the box in Cortese’s Fort Collins home.

Flipping through old letters, pictures and newspaper articles, Cortese now talks about his inventions, grandkids and his life with his second wife, Deborah.

Deborah, he reiterates. Not Debbie.