Wolff: The media versus Donald Trump

Never in modern history has the news media been so united in its condemnation of a presidential candidate and in its determination to use its influence to help prevent his election. Does that mean the election is rigged?

It is certainly a new view of the media function. The media’s sense of civic duty, in even the most high-minded view, is not about protecting the public, but about orchestrating the claims of people and institutions who think they can protect it. The natural competitiveness of the media business, and market sense that moralizing makes for a duller story, have, arguably, helped pluralism and democracy. The media is not a church.

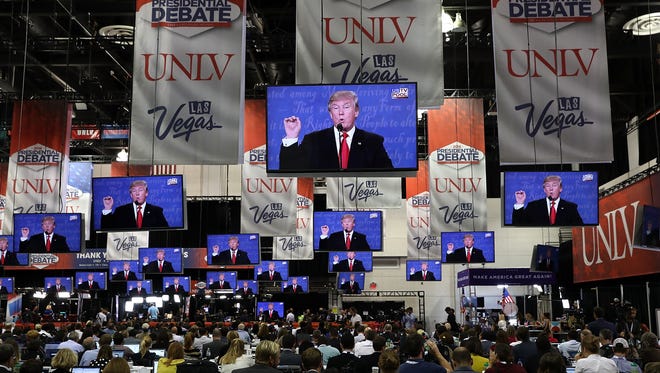

But now it is. Or, save for a few outliers, it is like one in its absolute certainty, and hell and brimstone warnings, that electing Donald Trump would be electing the devil. Since September, when the polls appeared to tighten, the message from newspapers, cable stations, networks and pundits, and from the social media echo box, has been as consistent as it might be from Sunday pulpits—or, for that matter, in Saturday union halls, or Thursday meetings of special interest groups.

The media, virtually all forms of it, virtually all aspects of its ownership, virtually all of its employees, on an institutional and operational basis, has come to see itself as a firewall against Donald Trump. Indeed, in an altogether new sense of itself, the imperative quite seems to be to prove it can be a firewall—that it can claim a historic role in the defeat of Trump and the election of Hillary Clinton. For a sense of mission like this, you would have to reach back to the media’s de rigueur patriotism during the Second World War, or to how it fell into line during the tensest years of anti-communism, or to the sense of national crisis in the months after 9/11.

Wolff: What Trump will win even if he loses

In this, Donald Trump, even having garnered a major party nomination and a base of support likely over 40% of the electorate, might fairly see himself as being treated differently from other presidential nominees, and, indeed, being effectively blocked from the possibility of being elected. The system is against him—that is, it’s rigged.

The media response to Trump’s protestations of a great rigging is, largely in concert, and helpful to its case against him, to deride him for suggesting that it is rigged. In fact, to use his claim as further evidence that he is not only not suited to be president, but it is he who is undermining democracy—in a sense a double rigging.

Trump, not especially helping his argument, has conflated voter fraud with his case against the media. It is undoubtedly much easier to understand the concept of voter fraud, however improbable, than it is to understand the actual change in the nature of the media.

Wolff: Why we embrace Trump as a 'businessman'

Traditionally, the media market likes a horse race—even a generally liberal media favors conflict over liberalism. This tends to flatten the built-in biases, at least in national races, and, in its way, to provide an amount of structural support for the principle of objectivity. An open contest and uncertain outcome are good for the media. But now the media is engaged in something like a massive self-correction. Having promoted Trump, turning him into an unlikely and compelling contender, it now, in remarkable unison, has decided he must be stopped. Almost all anti-Trump partisans would argue the virtue of this position. Still, it is also hard not to see this as, also, a select group of powerful people and institutions going out of its way to put a brake on popular will.

There is, here, an interesting answer to the long-asked hypothetical question of what if there arose in America an authoritarian figure and fascist sort with wide popularity. The answer, at least in this instance, is that the media would represent the norm and, in concert, ridicule, belittle, shame the offending candidate, and in a myriad of other ways prevent the repugnant message from moving mainstream.

In this, the singular and overwhelming power of the media—in which an outsider candidate so appalls the civic standard that even a fragmented media unites in horror—might, not unfairly, seem to represent the exact sort of elite that Trump has been campaigning against. Indeed, Trump’s inartful campaign against the biased and crooked media has surely had the effect of making the media more determined to do him in.

Rieder: Trump, reality TV overwhelm the campaign

So he’s right, in his way. Or, at least he has defined a peculiar paradox. Trump is not just an extreme candidate, but an inept one, unable to make the slightest ritual bows to propriety—like basic debate preparation—that might have forced the media to have defaulted to at least grudging neutrality. Indeed, by violating all the norms, Trump has become not just extreme and inept, but absurd. How could any sentient person or institution take him seriously? Pay no attention to the large minority of, by definition, lack of sentient people, who do.

Of course, if you’re going to rig an election, you want to rig it in the direction it might seem plausibly to have gone anyway. Hence, in this rigging, a large majority will surely applaud the outcome—so, in that sense, the voters voted for the rigging. Therefore, ipso facto, it’s not rigged.

Except that there is no way under the sun that Donald Trump was ever going to be elected president.