Is Obamacare failing? No. Flaws? You bet. Fixes? We'll see.

Guy Boulton

Guy Boulton

Republican politicians rarely mention Obamacare without adding the adjective “failing.” It happened repeatedly even last week when GOP senators were explaining their failure to repeal "failing Obamacare."

But is Obamacare really failing?

“In Wisconsin, it would be a tough argument to make that the market is failing,” said Marty Anderson, chief marketing officer for Security Health Plan, an insurer affiliated with Marshfield Clinic. “For the most part, there’s still a competitive landscape in Wisconsin.”

The same goes for most parts of the country.

This doesn’t mean the Affordable Care Act has worked out entirely as expected or as supporters had hoped.

Its biggest problem: Among Americans who don't get their insurance through an employer, not enough healthy people signed up for insurance on the Obamacare exchanges. That led to losses for insurers that participated in those marketplaces, which in turn led some insurers to either drop out of the marketplaces or raise their premiums sharply.

Problems, yes. But failing?

“Clearly it has some issues that need to be fixed, and if we had adults in charge, we would fix them,” said Len Nichols, a health economist and director of the Center for Health Policy Research and Ethics at George Mason University. “But we don’t, so here we are.”

RELATED:How Obamacare became a political football

RELATED:Covering people with pre-existing conditions is popular, problematic

On the plus side, the law has expanded health insurance coverage to roughly 20 million people who didn't have it before. It has enabled people with pre-existing health conditions to get health insurance that likely would have been denied to them before.

And, Nichols said, health care spending overall has increased at the slowest rate for any seven-year period since the 1960s.

“It’s not falling apart," Nichols said. "It has some flaws that could be fixed. But it is helping very significantly 20 million people.”

Here are two figures from the Kaiser Family Foundation for Wisconsin:

- 179,211 people who bought health plans on the marketplaces set up under the Affordable Care Act as of February were receiving subsidies that cap the amount they have to pay for health insurance to a percentage of their incomes.

- 852,000 people under 65 were estimated in 2015 to have a pre-existing medical condition that would result in their being denied health insurance in the individual market if it weren't for the Affordable Care Act.

Although Wisconsin did not accept the additional federal dollars available through the law to expand its Medicaid program, the law enabled the state to extend coverage to people who do not have dependent children and who have incomes below $12,060. In June, 144,003 people had insurance through that expansion.

And the number of people without health insurance in the state has dropped by an estimated 195,000 people, according to the University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute.

Wisconsin is among the healthier insurance markets in the country, in large part because of the number of regional health insurers affiliated with health care systems.

“At the end of the day, it’s been a very competitive market,” said Rob Plesha, vice president of actuarial services for Quartz Health Solutions, which oversees Gundersen Health Plan and Unity Health Insurance, in Sauk City.

The two health plans are close to break-even, Plesha said. And Anderson said the same for Security Health Plan.

Other analyses, including one by S&P Global Ratings, have found the same trend nationally. Also, the Congressional Budget Office has said the overall market for health insurance sold directly to individuals and families was stable.

There are parts of the country, though, where that doesn't hold.

No insurer has committed to selling health plans on the marketplaces in about 40 counties in three states — Indiana, Ohio and Nevada — next year, according to an analysis by Katherine Hempstead, a senior adviser to the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

The analysis projects that:

- The percentage of the population that lives in a county with one insurer may increase to 25% next year, up from 20% this year.

- More than 75% of the population will live in a county with two or more insurers next year.

- A bit more than 50% of the population will live in counties with three or more insurers.

The counties with only one insurer generally are rural counties with fewer potential customers. Hempstead expects state regulators will work hard to ensure that every county in their states has at least one insurer.

“I’m cautiously optimistic that there won’t be any bare counties,” she said.

Even in Wisconsin, the market remains somewhat in flux, with large national insurance companies such as UnitedHealthcare and Humana having pulled out of marketplaces. J.P. Wieske, the state's deputy insurance commissioner, characterizes Wisconsin's market as fragile.

So, too, does Cathy Mahaffey, the chief executive of Common Ground Healthcare Cooperative.

“We know that not enough healthy consumers have enrolled in insurance and that costs are too high,” Mahaffey said in an email. “While we are seeing more positive results in 2017, that does not mean that the market is now all of a sudden stable.”

The failure to draw enough healthy people into the market to offset the cost of covering people with health problems may be the most significant problem still facing the market.

The result has been higher medical costs paid by insurers and higher premiums for people who don’t receive federal subsidies.

Many of them have health plans with more generous benefits than they had before the Affordable Care Act. But that’s typically faint consolation.

“Those are the losers,” Hempstead said. “Do I think that the winners won more than the losers lost? Yes. But the fact there still are losers means that there are ways to improve the policy.”

Two potential fixes

One solution could be a reinsurance fund to cover very high medical claims.

“It’s a potentially pretty sensible way to go forward,” said Justin Sydnor, a professor of risk management and insurance at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “There are good economics behind that.”

Karen Bender, president of Snowway Actuarial and Healthcare Consulting in Little Suamico, also recommends allowing insurers more flexibility in designing their health plans, enabling them to offer lower-cost plans with fewer benefits that would appeal to more to people who are healthy.

Mahaffey of Common Ground Healthcare Cooperative and other insurance executives have said the same.

Both proposals would require legislation.

“Those are the kinds of things that frankly members, in the Senate anyway, on both sides of the aisle could agree upon if they were free to pursue a solution as opposed to the political game of casting blame and trying to repeal the whole thing,” said Nichols, the health economist at George Mason University.

He also recommends increasing the subsidies slightly and increasing the penalties on those who don't buy insurance.

The immediate question, however, is whether the Trump administration will instead take steps to undermine the insurance market. If the administration were to choose not to fund the subsidies that help low-income people afford insurance, for instance, the entire market could be upended.

The administration also could undermine the law by not enforcing the mandate that people have health insurance or pay a penalty.

Polls, though, are showing wide public support for fixing the problems with the Affordable Care Act rather than gutting it — and for bipartisan reform.

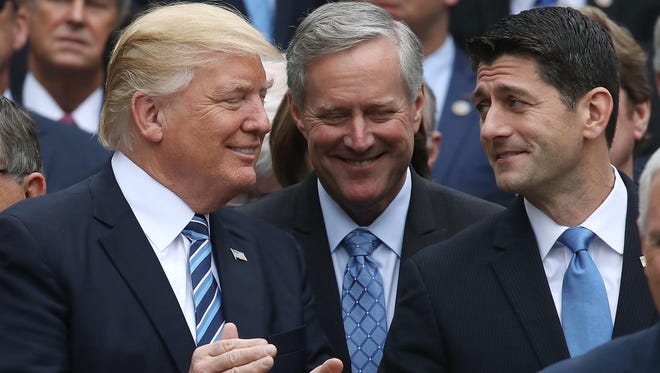

Nichols notes that President Donald Trump said during the campaign that his health care reform plan would provide coverage for everyone.

“Leaders in both parties have to admit that they share goals,” Nichols said.

Republicans need to admit that some people were helped by the Affordable Care Act, he said, while Democrats need to admit that some people were harmed by the law.

That could provide a bipartisan path to fixing it.

“It can be done. It’s not rocket science at this point,” Nichols said. “But it does require a level of honesty and political courage and a willingness to acknowledge that the other side has a point.”