Milwaukee-area communities are using tax incremental financing more than ever to fund developments, but not everyone likes it

Jim Riccioli

Jim Riccioli

If you want to start a public policy debate, round up a group of local government officials and residents from different backgrounds and say "tax incremental financing."

Anticipate a buildup of emotions, especially involving suburban communities where TIF districts have huge success stories.

Some firmly believe in this form of development incentive. Others view it as a straight-out bad deal for taxpayers, a criticism that tends to emerge especially when a project is unpopular with neighbors.

Either way, officials say, it is the only meaningful economic tool that Wisconsin has handed local governments, responsible for numerous projects ranging from industrial development to higher density residential projects, with varying success rates.

Deciding which projects merit this form of public investment is the key.

"The big picture is, obviously, if you're committing a dollar of TIF money to bring in a large development, then that's a great use of the money, as an absurd hypothetical," said Jason Stein, research director for the Wisconsin Policy Forum, a statewide nonpartisan, independent policy research organization with offices in Milwaukee and Madison.

"On the other end of the absurd range, if you're using TIF to make an investment that will take 100 years to pay off, it's a really bad use of the money, right?" Stein said. "In real life, it's never that clear. Or it's rarely that clear. It's a question of making judgment calls."

Wisconsin Policy Forum's own research suggests that the use of tax incremental financing by local governments has never been more popular, in terms of the establishment of new TIF districts.

Citing Wisconsin Legislative Fiscal Bureau data, Wisconsin Policy Forum's February 2019 report said state municipalities used $4.1 billion of new property tax revenues derived from TIF districts to support private development and public infrastructure within those districts between 2007 and 2017.

In 2017 alone, $472 million was used, an increase of 25% compared to 2007 (adjusted for inflation).

So what's it all about?

The theory behind TIF

It starts with a strategy allowed under state laws in which a developer can tap into a community's future earnings by promising, contractually, to improve a property or land parcel enough to generate new property tax values, well beyond what the property generated before the development began, to make it all worthwhile.

In doing so, however, taxes are diverted for a period of two decades or more to pay debts associated with a development. That means the community as a whole doesn't see the money flow into the tax coffer until after the debt is retired.

That rankles some TIF district opponents, who see it as a tax subsidy primarily benefitting developers who could choose to finance projects without public assistance.

But proponents said such thinking excludes an important reality: Without a tax-funded incentive, developers would either shy away from certain high-value, high-cost projects or simply move on to the next community which more actively supports such an incentive.

Here's how it works

To the average resident, tax incremental financing isn't something that's thoroughly understood. Some mistakenly believe that developers granted TIF dollars don't have to pay their taxes. Others think of it as entirely free money going into developers' pockets.

In reality, there is no tax break at all. In fact, as a development proceeds, the amount in taxes increases, a necessary component under the contractual arrangement between a municipality and a landowner.

In TIF districts, the "increment" refers to property tax dollars generated above and beyond the taxes paid before a new development or redevelopment begins. That increment, instead of going into the municipality's revenue fund, is diverted to pay for other aspects of a development project, usually for public improvements or certain redevelopment costs.

Let's say a property valued at $1 million is paying $15,000 in local property taxes every year. A developer sees greater potential and takes out an option to buy the property to build a $10 million project, but only if the developer can obtain TIF dollars to finance the costly plan.

Under that scenario, if a TIF district is created, the property owner would continue to pay the $15,000 every year, which continues to be distributed to the various tax jurisdictions. But as the project advances and is completed, the taxes generated by the additional $9 million in value, also paid by the landowner, would be diverted to pay off the development debts for a set period, usually 20 to 27 years.

Those new property tax dollars would not end up in the coffers of the various tax jurisdictions — typically the municipality, the school district, the county or the technical college district — until the development debt is retired.

Because those tax jurisdictions are each affected by a decision to create a TIF district, each has a say at the outset over whether one should be approved. Each jurisdiction is represented on what's called a joint review board, which also may include an at-large member. A majority vote is needed from that panel before a TIF district can be set up.

TIF stories and successes

If a TIF district achieves its goals within the timeframe set up at the start, it is considered a success. Some do so well that the TIF district can close earlier than contractually required.

A few such examples stand out.

Waukesha

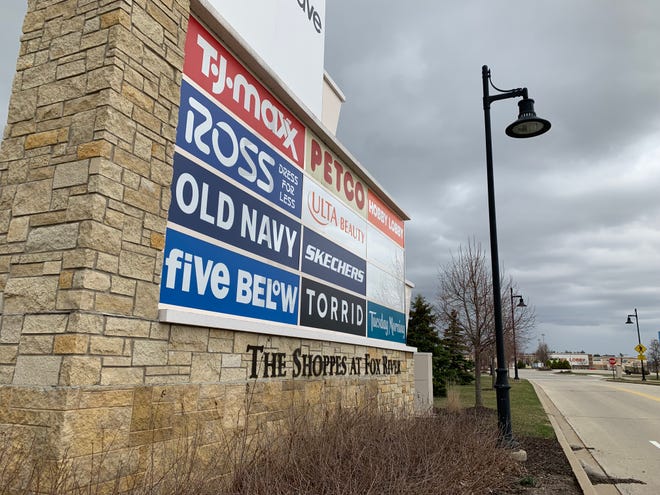

Perhaps the most successful, as determined by how quickly the debt disappeared and how prominently the development stands in a community, is TIF District 14, which includes the Shoppes at Fox River in the city of Waukesha.

Kevin Lahner, Waukesha's city administrator, said that development alone is proof how well tax incremental financing can work for a community intent not only on economic development, but refurbishing rundown properties.

"It's almost a textbook TIF deal, in how to do one and have a high level of success in creating value," Lahner said, noting that the debt on that TIF district closed in 2021, years earlier than required, largely as a result of the 467,000-square-foot shopping center.

In 2018, a decade after Shoppes took shape, the city's development director, Jennifer Andrews, likewise praised the development's role in enhancing the city's revenue and aesthetics.

"We see the Shoppes at Fox River as a great success," Andrews said. "The development transformed a vacant distribution center with a value of $7.3 million to a vibrant neighborhood shopping area serving the southwest side of the city with a $60 million value."

Lahner said Waukesha has also invested TIF money in its downtown, particularly for recent apartment projects, including Mandel Group's BridgeWalk Apartments on St. Paul Avenue on what was once a railroad property.

"If we did not have TIF, we would not be having the renaissance we are having downtown," Lahner said. "Because the cost would cause the developers not to do projects."

Oak Creek

For Oak Creek, the creation of a TIF district to create the city's true community center is equally as important as the Shoppes at Fox River were for Waukesha. More so if you consider that the development incorporated the city's main municipal offices and library as well as upscale apartments within a commercial center.

The development's value is expected to climb to at least $220 million by 2032, when the city's debt is expected to be retired just 19 years after construction started. All at what was once the Delphi Corp. auto parts factory.

"It just created more of a dynamic environment than you would expect to see in a community like this," developer Blair Williams, whose buildings there include both apartments and retail space, said in 2016.

Oak Creek has continued using TIF dollars to enhance its business center.

Mequon

In Mequon, an Ozaukee County community that has been traditionally light on TIF districts, the desire for the development of a central business district has led to similar investments, including a 2018 plan.

The city has used the incentive funding for Mequon Town Center, but the Foxtown add-on development aspired for more. Before the project, the land generated $16,500 in annual tax revenue. According to city officials, the $51 million Foxtown will eventually generate $800,000 in annual tax revenue, all in exchange for $4.95 million in public funds phased over five years, through 2023.

Wauwatosa

Wauwatosa has likewise used tax incremental financing to rehab old industrial areas into modern, highly sought uses.

In 2013, a plan for the former Western Metals site took shape, eventually resulting in a project to build upscale apartments. In 2018, a plan to convert a former office building into a four-star Mayfair hotel gained support after the city offered $13.8 million to support the project, which is expected to create $53 million in new value.

Generating public debate

Success doesn't always sway some people — public officials or residents — who oppose TIF districts. Other factors lead to a debate that never seems to end, even as TIF districts continue to take up space in municipal borders across the area.

Stein said Wisconsin Policy Forum, which has addressed TIF as a public policy several times in its research efforts, acknowledged that local governments need to tread carefully in their decision making, not solely giving in to pressure by a developer.

"The argument is that if (developers) don't get a TIF, a project will just go somewhere else; that by itself is not a reason to do a TIF," he said. "The only reason to do it is if the project makes sense."

Stein said resistance to TIF as a fundamental concept does exist. What's important to keep in mind is that local government units in Wisconsin can do little else to spur development within their communities, Stein noted.

"The thing about TIF is it's really the only tool that local governments in Wisconsin have to do economic development to try to attract companies, employers, housing developments — all that stuff," he said. "So, if you're saying that a local community shouldn't do any TIF deals — a position a rational person could have — you need to understand what it's saying, that a local government shouldn't be directly involved in economic development."

Among those who have voiced concern loudly enough to gain public attention is state Sen. Duey Stroebel, R-Cedarburg, who Lahner listed as someone who seems to detest the tool as policy. And that includes new legislation approved in March.

As chairman of the Senate Committee on Government Operations, Legal Review and Consumer Protection, Stroebel helped usher through a bill authored by State Sen. Joan Ballweg (R-Markesan) that requires TIF deals to have more public transparency.

In a statement after Act 142 was signed into law by Gov. Tony Evers recently, Stroebel noted the new transparency provisions "will make sure the right data is being collected and reported to the Department of Revenue so we can correctly analyze how tax increment financing ('TIF') interacts with levy limit and revenue limit laws to impact property taxes."

The law will also require municipalities to report the property tax impact of TIF deals as part of their annual reports.

Even closer to home, Lahner has seen resistance in Waukesha.

Frank McElderry, an alderman whose district includes the southwest corner of the city, indicated in a recent interview that he thinks TIF districts should not be set up as broadly as the city has in recent years.

McElderry, who sided with neighbors who opposed a recent proposal for a 72-unit apartment complex off Saylesville Road in an area where TIF districts have been used to jump-start similar projects, didn't rule out the use of tax incremental financing in general. But he questioned whether TIF dollars should be directed at any open developable parcel without good reason.

For instance, he accepted the TIF proposal for new BridgeWalk Apartments on St. Paul Avenue, similar to other downtown areas that need redevelopment, but said that doesn't mean the economic development tool should be employed elsewhere.

"Downtown development is needed. However, I am not in favor of TIF districts unless it qualifies for a blighted area," he said.

Perhaps more famously was a statement by Norm Cummings, a now-retired administration director for Waukesha County who served on a joint review board that seemed destined to turn down a proposal to extend TIF District 14 to incorporate Mindiola Park and other areas along Sunset Drive.

The fact that Cummings did not favor the Mindiola plan was not surprising. Others shared a concern that the plan to build a city-owned ballpark on the site as the basis for spurring economic development nearby was a nontraditional use of TIF dollars.

But Cummings, in board discussions, also intimated that he likely would have opposed TIF District 14 from the start, when developers first proposed the Shoppes at Fox River.

Even in Mequon, which has ranked the lowest in the metro region in percentage of new development dollars tied to TIF districts against the overall equalized property values in the community, the mayor is careful to stress the city's reluctance to invest too often in developments.

"Mequon has been exceedingly careful. That is the way we do things," Mayor John Wirth said in his 2019 campaign website.

In Bayside, residents opposed a mixed-use development — a 27.4-acre project would bring 350 to 450 apartments and housing units and a new North Shore Library — using TIF dollars. Those residents, under the group called No Bayside TIF, sued the village in January, claiming that the meetings in which the plan was approved were invalid.

Lahner said he sees some opposition to TIF districts arising not from the funding tool itself but from a specific development that residents simply oppose.

"For the folks that don't like TIF, I think their arguments are fundamentally flawed," he added.

It is possible to TIF districts to fail. That happens if a development fails to produce enough new taxes to pay off the outstanding debt. But Lahner said communities have successfully avoided such scenarios.

The key, Lahner said, is for communities to draft development agreements carefully, making sure a developer shares the burden equally and has the financial figures to back up projections of increased value.

Stein acknowledged there is sometimes an ideological divide among people who argue for and against tax incremental financing.

"Yeah, I think a lot of economists would say that it would be better for a government not to pick winners and losers," Stein said. "At the same time ... local governments may want certain amenities in a development that would be things people in the community want. And they make a judgment that the market wouldn't provide those things and TIF is a way to get them.

"I think a lot of this stuff comes down to people exercising good judgment."

Contact Jim Riccioli at (262) 446-6635 or james.riccioli@jrn.com. Follow him on Twitter at @jariccioli.